I thought of my next book’s title: “How to Become Broke and Influence Nobody.” Yep, last night while making dinner (okay, heating up leftover chili cheese fries), I realized I’ve had so many crappy jobs, all while making absolutely no money, I could fill an entire book.

I’ve been an awful waitress (After spilling a tray of filled beer mugs on customers, they returned another night wearing yellow raincoats), a bad showroom model (I accidentally insulted a designer), a terrible receptionist… a not-so-great aerobics instructor.

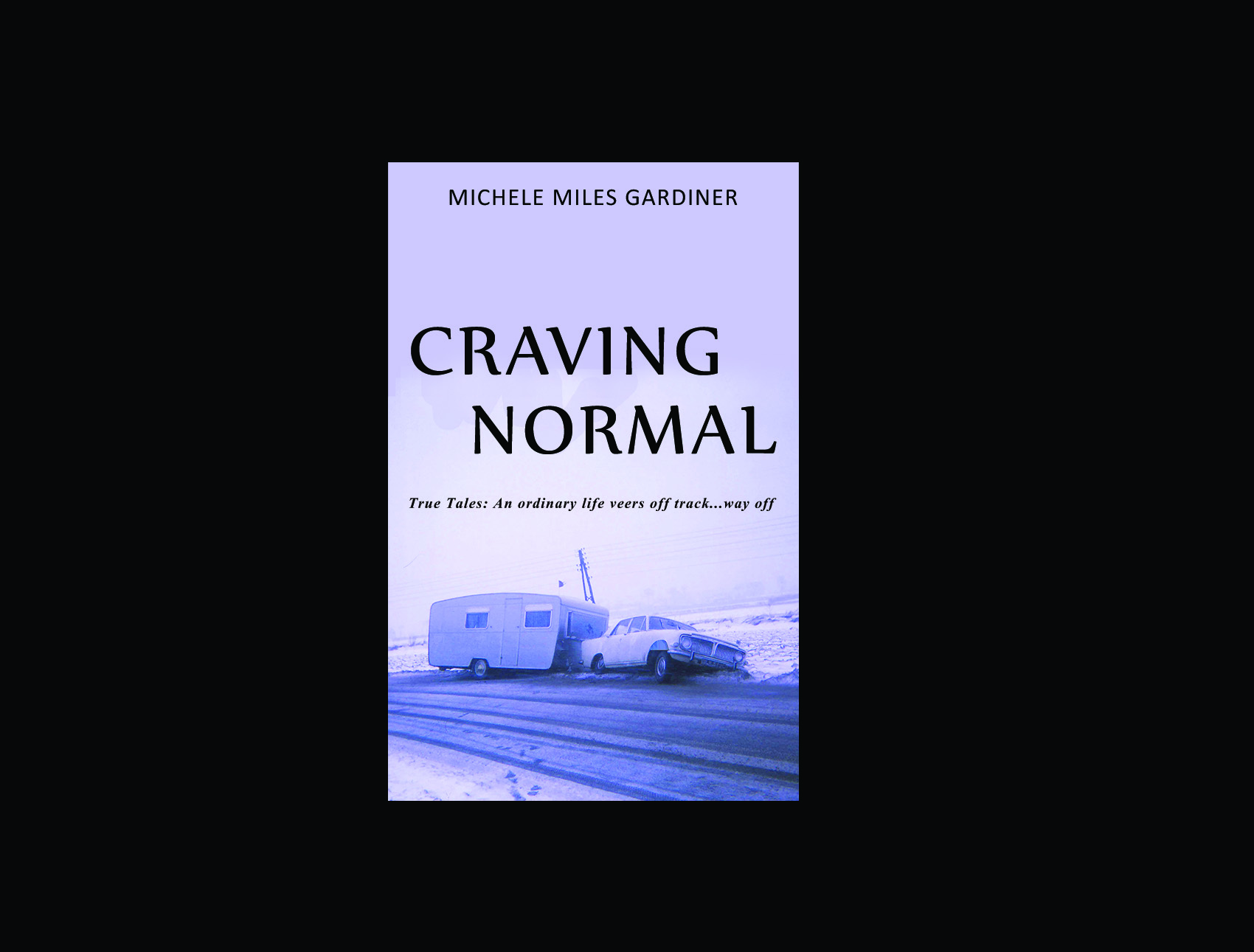

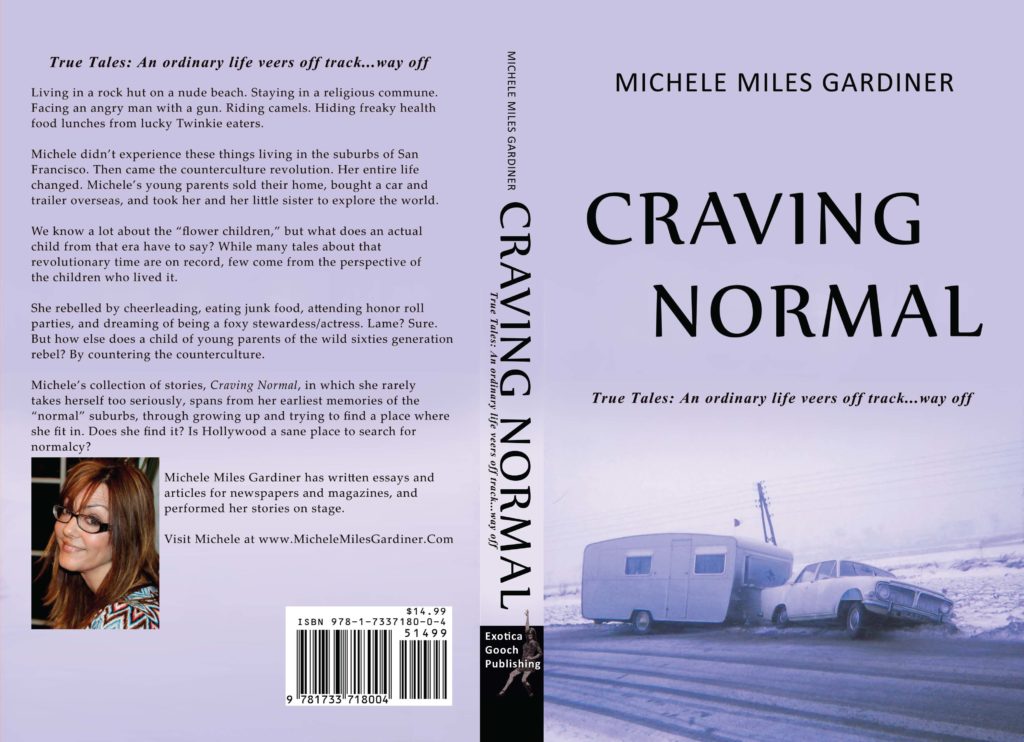

Well, here’s an excerpt from my book, Craving Normal.

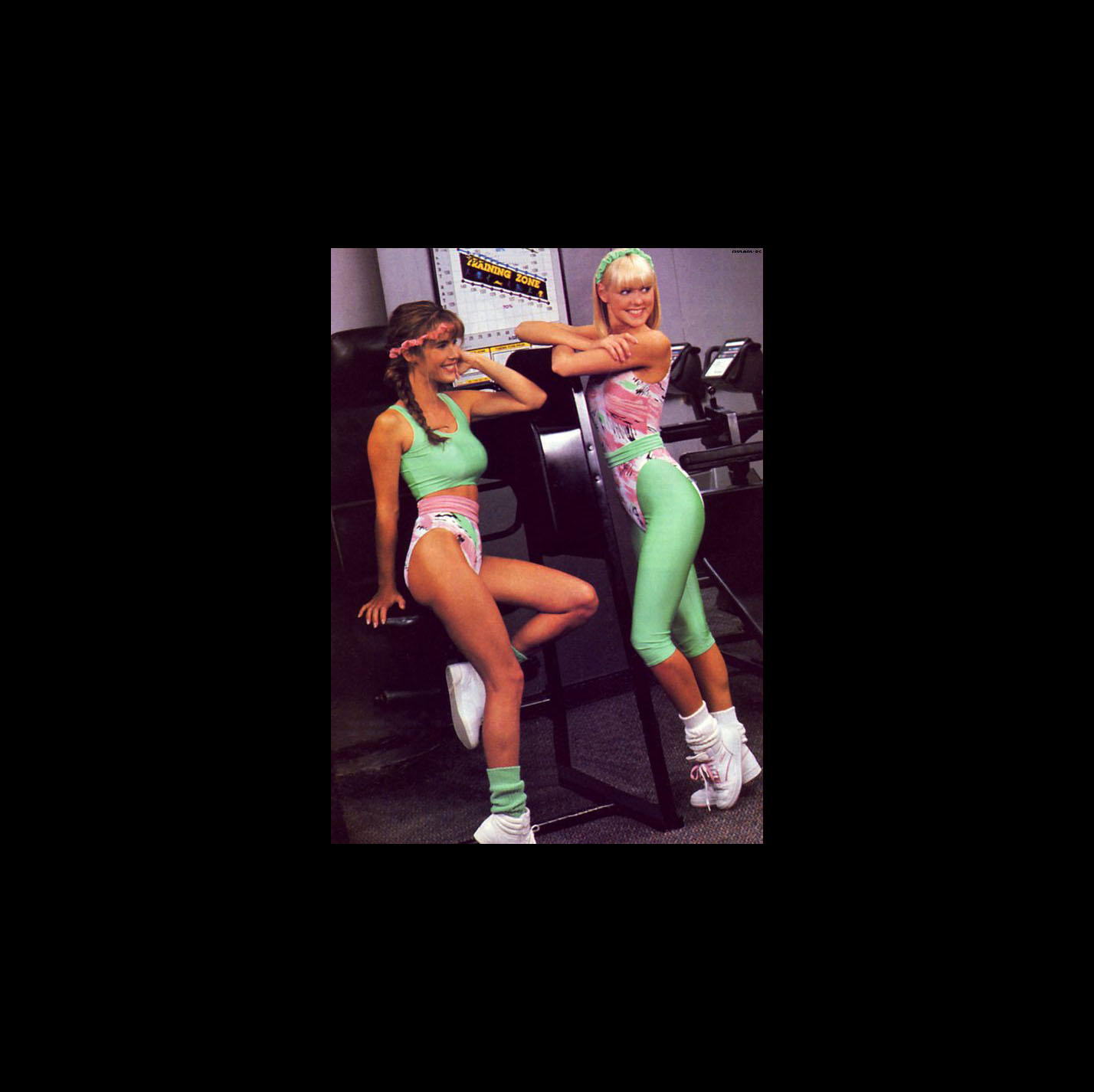

While working as a movie extra, I got a second job as an aerobics instructor. I figured, why not get paid and get in shape? But I could only bounce my way to a tighter butt and shin splints at minimum wage for so long.

A few months after working at Holiday Spa in Torrance, I called in to let my manager know my car overheated and broke down. Since I was living in Hollywood—nearly an hour drive away from work—I wouldn’t be able to make it that day without a car. That’s the way I figured it, anyway. But my manager “helped me out.” She said, “No problem. Kimmy lives in your area and can pick you up on her way to work.”

I yelped a fake, “Great,” and shuffled off to get ready for Kimmy, a cute blonde aerobics instructor, to pick me up.

Wearing my aerobics outfit—nothing more than a tiny shirt, tights under black French-cut bikini bottoms, big, poufy socks, and white bouncy shoes—I waited on the sidewalk in front of my apartment. Kimmy pulled up to the curb, and I jumped in. Right away, we bonded. Not only were we both out in public wearing little clothing, but after talking, we learned we were both burned out from being bubbly every work day. We agreed we were tired of cheering people on to tighter thighs. “Come on, ladies! One, two, three, four, keep it up—just a little more! Five, six, seven, eight. Keep going. Doing great!”

We drove through the palm tree-lined streets and headed south toward the Torrance Holiday Spa via PCH, parallel to the ocean. It was a stunning summer day. As we passed the sparkling blue water of the Pacific and tanned guys carrying their surfboards, Kimmy said, “Wow, the sky’s so blue. Beautiful day.”

“Yeah,” I agreed, looking toward the beach and the tanned guys, “and . . . so hot.”

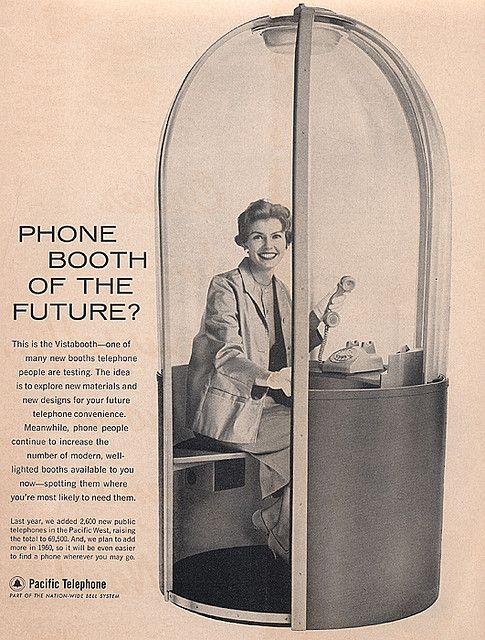

We looked at each other. I knew what she was thinking. She knew what I was thinking. The beach was way too tempting. Kimmy stopped at a pay phone and called in to the spa. “You won’t believe our luck. My darn car overheated. Can you believe it?”

Somehow, I don’t think they did.

Please follow and like us:

Photo 1: Tommy Gelinas, the man who runs this fascinating and fun museum. His energy is as luminescent as his vast neon sign collection.

Photo 1: Tommy Gelinas, the man who runs this fascinating and fun museum. His energy is as luminescent as his vast neon sign collection. Find Craving Normal at

Find Craving Normal at